Foto: Arno Mikkor

Trump’s Second Act?

Europe can survive Trump again – if Germany leads

By Tara Varma

Let us imagine that it is November 2024 and Donald Trump has won the US presidential election. Europeans are worried, scared and preparing for the worst. But they are not shocked as they have already lived through one Trump presidency.

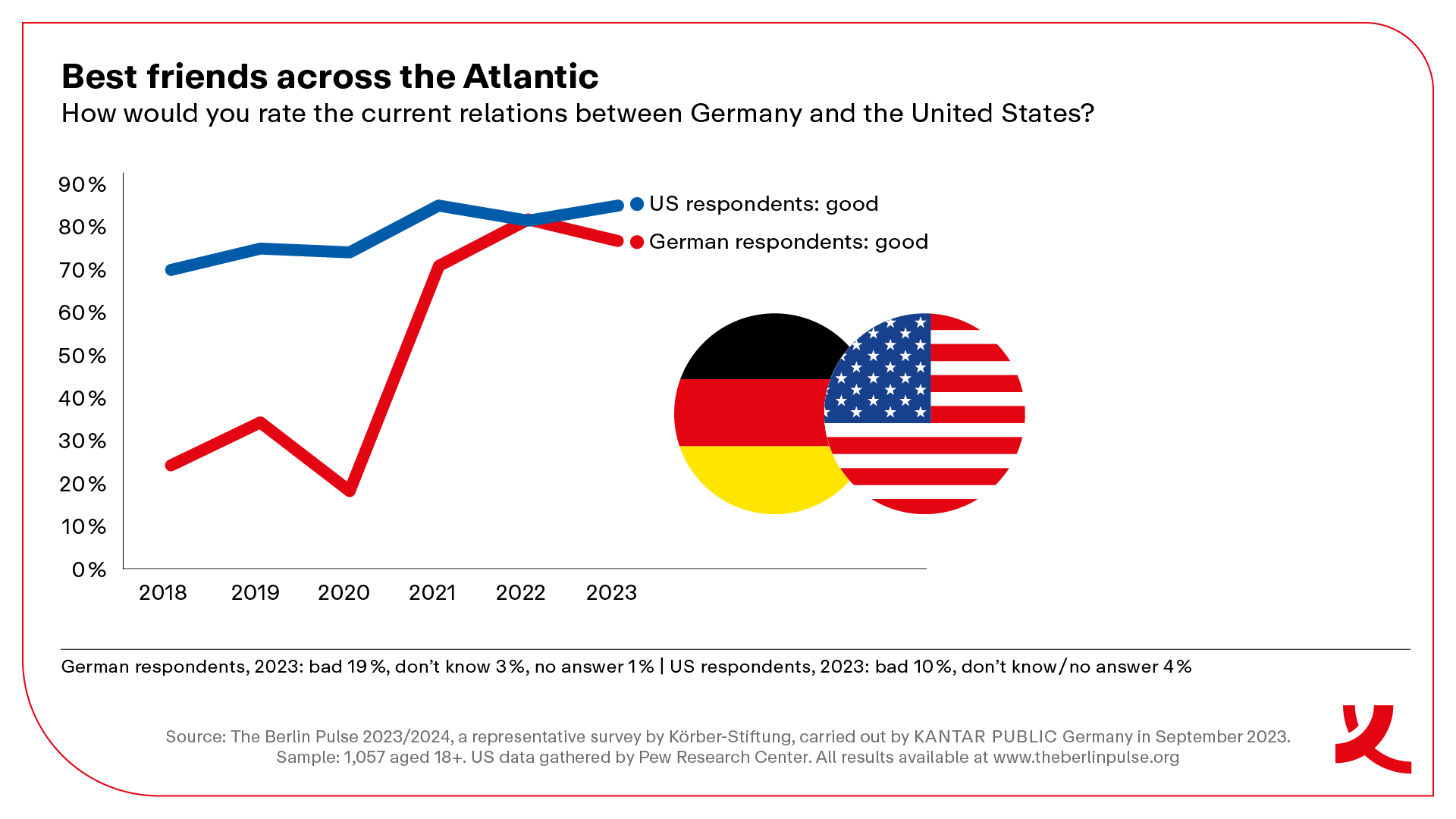

Europeans remember the fundamental crisis Trump brought for the transatlantic relationship in his first term. He withdrew the United States from several multilateral agreements, such as the Paris climate agreement and the Iran nuclear deal. They also remember that during the COVID-19 pandemic the Trump administration fought Europe for vaccine access and banned Europeans from entry into the United States for months, while Americans could still travel to Europe with no restrictions. And Europeans have not forgotten that Trump considered withdrawing the United States from NATO. The US security guarantee is existential for most European states – inside and outside the European Union.

But from COVID-19 then to Ukraine now, Europe has become stronger. It responded to the pandemic with financial solidarity, breaking the taboo of common borrowing at the EU-level, and purchased common stocks of critical drugs and medical equipment. Germany’s reversal of its frugal position especially paved the way for the change in the EU’s position. Europe also jointly and decisively responded to the shock of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Germany is now well into the second year of its proclaimed change of era, the Zeitenwende.

In the worst-case scenario, Trump withdraws the United States from NATO. It would immediately end the credibility of the US security guarantee to Europe. It would also mark the end of the Western alliance, and – maybe more importantly – the end of Ukraine as a country. Putin would see this move as a nod to pursue his attacks not just on Ukraine but probably also on other countries in Eastern Europe, such as Poland. Meanwhile, Trump would also pursue strategic decoupling from China, including by raising tariffs on Chinese goods. These steps would plunge the transatlantic relationship in agony. They would also put Germany in an untenable situation: having long relied on the United States for its security and on China for its economy, it would suddenly be left with neither.

In a second scenario, Trump would only threaten NATO withdrawal should Europe not contribute more to its defence. This would leave Europeans considering a future on their own, faced with a revisionist and dangerous Russia as well as a revisionist China intent on keeping its access to the European markets while further destabilizing the broken transatlantic bond. Trump’s unpredictability would make a comeback. He would make grand announcements and then walk them back. He would post rants against Europeans on social media, leaving them clueless as to whether they should take him at his words or not.

Finally, there is, if not a best-case scenario, at least a leastworst one in which Trump upholds the US commitment to NATO in exchange for not only an increased European financial and material commitment to Europe’s defence, but also more European engagement in the Indo-Pacific and alignment with US policy in the region. Europeans are preparing for these demands. But a major question lingers concerning the coordination for transatlantic cooperation in the Indo-Pacific. If not through NATO, an organisation Trump despises, then how should this coordination be achieved? Europeans, too, notably disagree on a potential NATO engagement in the Indo-Pacific.

With this comes the expectation that Berlin is finally going to take on the responsibility of being a leader in European defence and security policy. As Germany undergoes this paradigm shift, so does the EU with its own one as it seeks to integrate geopolitics into the European peace project. When it comes to Ukraine, Trump has vowed that, if elected, he would immediately bring Presidents Volodymyr Zelenskyy and Vladimir Putin together and ‘end the war in 24 hours’. He also pledged to ‘finish the process we began under my administration of fundamentally re-evaluating NATO’s purpose and NATO’s mission’. Europeans hear alarm bells ringing. Three scenarios are possible.

In any of these scenarios, Trump would be very willing to divide Europeans and to pit them one against the other. To prepare for all these scenarios, Europe needs a common strategy and defence policy. Germany was among the most reluctant EU member states in this regard before Russia’s full invasion of Ukraine. The Zeitenwende coupled with its first National Security Strategy present a roadmap for change. However, for change to be sustainable in the long run, Germany will bear a special responsibility to ensure that investments in Europe’s defence are not just cyclical but also truly structural. These will need to be made inside and outside NATO.

In the face of Trump’s possible return to the White House, Europeans should pursue a more balanced transatlantic partnership, in which they take greater charge of their security and present the United States with an offer it could not refuse: more investment in their own defence capacities and more involvement in the Indo-Pacific region.

Tara Varma is a visiting fellow at the Centre on the United States and Europe at the Brookings Institution and former senior policy fellow and head of the Paris office of the European Council on Foreign Relations