(c) Lawra Vlzqz/Flickr

With Digital Technologies “You Can Get Closer to the Past”

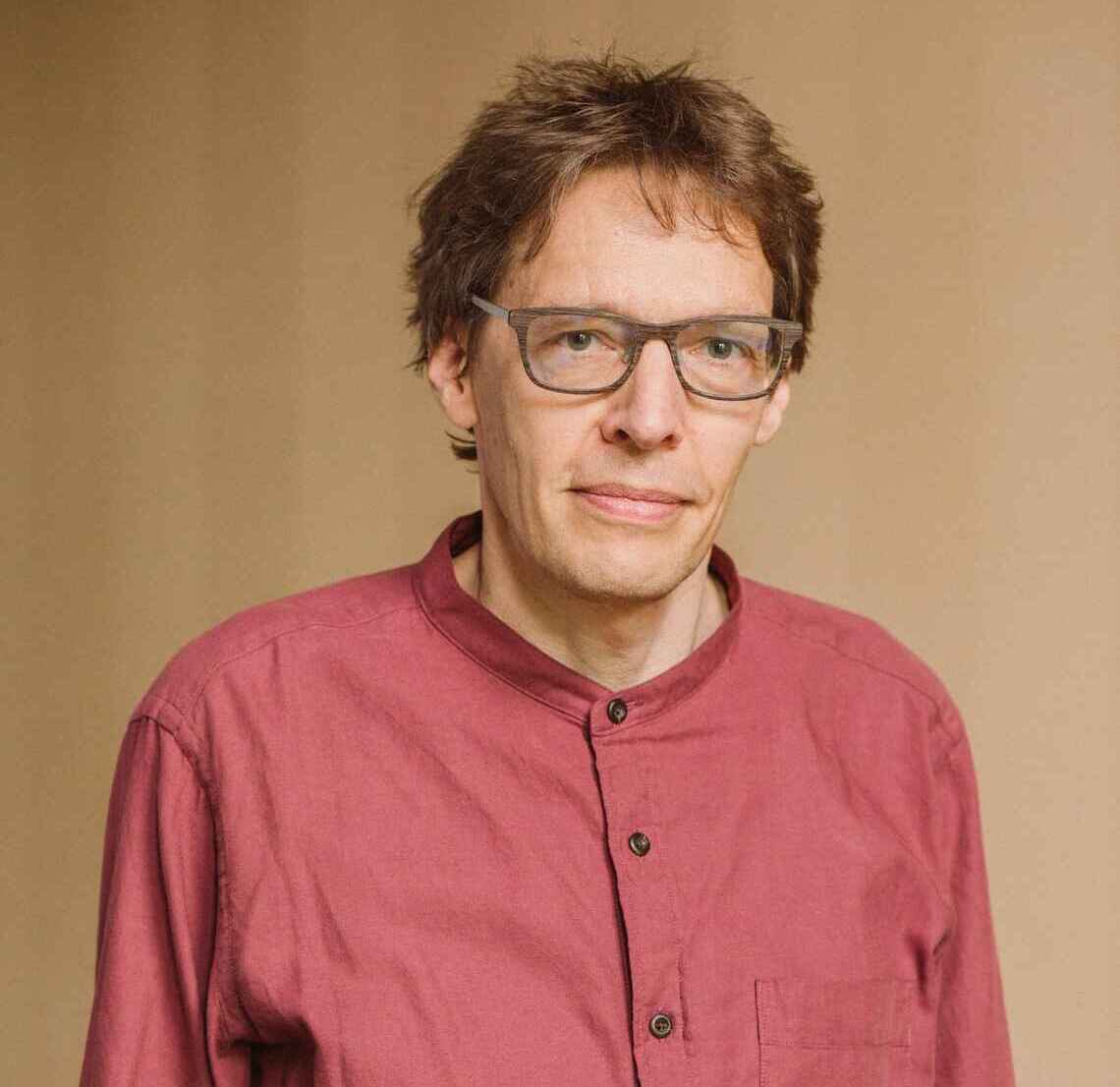

Popular culture, comics, visual images – Kees Ribbens is fascinated by the way history is represented in different media. He is a senior researcher at NIOD Institute of War, Holocaust and Genocide Studies, and concludes that our definition of the past is always limited.

Your Twitter profile says that you are interested in how World Wars and genocides are represented in “popular historical culture”. What makes this field so special?

Kees Ribbens: All kinds of ways in which history is represented are relevant. The reason why I am particularly interested in popular culture is that I have the impression that the representations of history in this area are usually neglected or underestimated. The reach of popular culture is quite large. Many of my colleagues, fellow historians or other academics do not take it as serious as their own academic output. But I think it is important to look at popular media forms. Not only because of their reach, but also because they create the possibility for innovation.

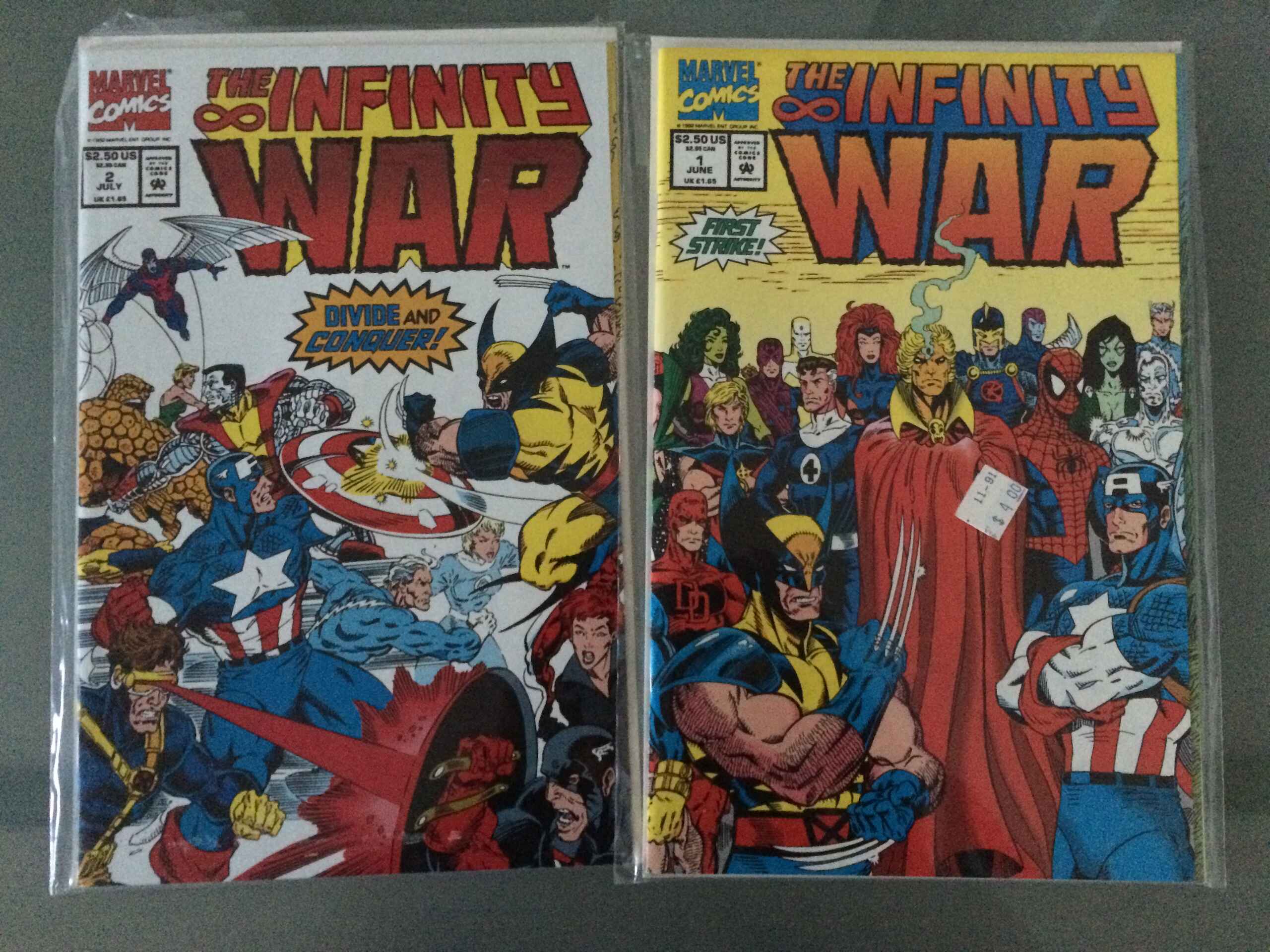

Is this why you’ve chosen to research comic books?

It wouldn’t be honest to say that my entire interest for comics comes from my academic point of view. There is some love for that medium involved in it. I’ve been a comics reader since I was a young boy and I’ve always been surprised by the lack of understanding of the medium. In the last 20 years, comics studies as an academic sub-discipline has evolved. But quite early on, especially among historians, there was an awareness that comics existed, and that history was represented through comics, but it was never taken seriously, because they thought it is a children’s medium. It is to some point, but when you look at graphic novels, most readers are adults. Even if you reach an audience of children, this can be quite influential if the images portray how a war is being fought, what being in a war really means.

How are these developments linked to today?

The media landscape has strongly evolved. There are so many channels available, everyone has social media, there are all kind of television channels, everyone can make their own video through YouTube or TikTok. But in the 1950s, 60s or 70s, when we were relatively close to the war, one way to get an understanding of the past was based on how it was presented in comics. They reached a large share of people, especially young ones. Some of the comics published back then are still available today, so there is a long-term impact. And the fact that a lot of these comics are coming from abroad makes them a kind of transnational memory culture. All these aspects make me intrigued by the medium and what it can do and how it has contributed to the memory culture of the Second World War and postwar decades.

You’ve just mentioned different digital technologies and how they redefine history – that is what we discuss at eCommemoration as well. What did you think when you first heard about our programme?

To be honest, I was a bit surprised that the programme is based in Germany, because people are very cautious about German memory culture. I was gladly surprised that the eCommemoration Convention was taking place in Hamburg. It’s about time we take these things seriously. It’s not that people who work in museums or memorial centres are unaware of new forms of media, but I think there is a certain fear. Modern media offers all kinds of possibilities, but it also means that we as institutes do not have much to say about the form, the content and what’s being told in these modern-day narratives. That kind of fear should be taken away. I’m not saying that games are the ideal medium to get a better understanding of the Nazi era, but there’s no single medium that is the perfect medium – even history books can sometimes be superficial. It’s about the right approach, critical questions, and about combining possibilities, options, and the potentials of different media. It’s great that an event like eCommemoration Convention is taking place, in which these things are approached from different angles. Plus, the fact that it’s not only scientists or academics gathering there, but also people from museums or with artistic backgrounds. That’s the kind of food for thought mixture that’s needed to progress the field of memory culture.

You were a panelist at last year’s eCommemoration Convention. During the discussion you mentioned that the definition of the past is always limited. Can you elaborate on that?

That’s the most essential thing about being a historian – you realize that even if you try to get as close as possible to the past, you will be extremely limited in what you can know. Even though visual material, visual sources are extremely important, I do think that a lot of narratives reach us either through text or through the spoken word. That already is a very limited representation of what actually took place. Everything that happens, happens in at least three dimensions, but is reduced to whatever representation of history. And at the same time, we’re talking about national and international history. Even if we’re talking about local history, we’re talking about hundreds, if not thousands of people. All these people have different experiences, all these people may have expressed their impressions differently. Some of them have been recorded, and if we’re lucky, we’re still able to read those things. We can try to record as much as possible but trying to do that on behalf of entire local communities, entire nations, and continents, that’s simply impossible without trying to reduce that to a certain number of elements. In that way, it’s always selective.

“Digital media can put people in a specific historical position, you can get immersed in certain historical circumstances. You can get closer to the past – although we need to be critical about that. At the same time, it offers a kind of safe environment in which you can include different positions, different perspectives.”

Kees Ribbens, Historian at the Institute for War, Holocaust and Genocide Studies

Digital technologies could broaden this perspective. What exactly are the potentials of commemoration in the digital age?

One the one hand, digital media can put people in a specific historical position, you can get immersed in certain historical circumstances. You can get closer to the past – although we need to be critical about that. At the same time, it offers a kind of safe environment in which you can include different positions, different perspectives. And I think that combination is essential. But we always must keep in mind that this is a reenactment of the past, so it always comes with limitations. With games you can be put in a certain time, but whenever you want to stop playing, you stop, you can just take off your headset, switch off your screen and you’re done. People in the 1930s and 1940s did not have that option. Of course, the average gamer will be aware of that, but that’s an essential difference that we must keep in mind.

Do we really need to relive the past to understand it? Do you see potential dangers in that?

Our societal role is to be cautious about the pitfalls and risks of what we’re trying to encourage. I think it’s a good thing to give people an understanding of what the past was like. But of course, we need to be careful, as this is always limited and selective. But if our aim is to improve people’s understanding of the past, of the Nazi era and the Second World War, then we have to make attempts to get closer to those events and to the impact they had. And also get closer to the motivations out of which they became possible. We cannot make it relatively easy and just identify ourselves with the feelings of the victims, we should also try to get some kind of understanding of what both, the perpetrators as well as the bystanders, were doing. And that’s not an easy mix.

Would you say, we concentrate more on the victims than on the perpetrators with digital media?

Our interest initially grows a lot out of trying to be empathetic towards the victims. And I think that’s an excellent and entirely legitimate starting point. If we were to go beyond showing empathy, beyond paying respect, it means that we also have to ask ourselves the difficult question: How did this become possible? Can we really understand the state of mind of perpetrators and their supporters? It is complex but I think we should – as kind of a continuous battle or discussion – try to get as close to that as possible.

Games, social media, VR – all these technologies present history. What influence does this fact have on the present lives of users?

On the one hand, they do help to keep history alive, keep it present. On the other hand, given the fact that it’s so easily accessible through different media, so omnipresent, it’s maybe losing a bit of its meaning. If you think of the Holocaust – it’s an exceptional tragedy – but the ways in which we can get access to representations of it are broad. I’m wondering if that doesn’t create some kind of inflation in meaning. It’s sometimes so present that I think it can also make people a little bit numb, making you less sensitive because you get confronted with it so often. Let me put it this way: Because it’s so omnipresent, because it finds its way through these new media, there is a certain risk that it might contribute to people becoming less sensitive about what it actually means. That combination of being omnipresent and partially being trivialized brings a certain risk.

In a few years from now none of the Holocaust survivors will be alive anymore. Especially younger generations won’t have the opportunity to get firsthand information about what happened during that time. How will this affect digital remembrance?

Witnesses of the Second World War have been dying ever since the war itself. And we’ve become very much aware, especially in the last 10 to 15 years, that there’s only a relatively small group of survivors still among us. At the same time, we’ve been trying to record their experiences as much as possible. There are interview projects, documentaries, people are invited to talk to survivors, people are asked to share their experiences, thoughts, and emotions. We’ve never recorded that many experiences from people ever before. But still there will be lacks in our knowledge. I think that witnesses or survivors play two roles. One is sharing knowledge. The other is that they give us the impression of being in direct contact with the past. It makes history more vivid. But I don’t think that connecting through interviews with persons is the only way. If you read an old diary of a person – which is very private – that can still create the impression that you’re getting closer to that person, even though it is one-way communication. Photos can also create some kind of intimacy. All these things are different, and they all come with certain limitations. But because we have all these different media options, we can overcome at least some of the gaps that occur when people pass away.

Let’s look into the future. 20 years from now, how will we commemorate, how will we perceive history?

I am a historian, I feel far safer talking about the past, but I am equally intrigued by what it will be like in the future. I believe that the user, the individual interested in history will become more important. My positive expectation is that there will be more space for the diversity of historical narratives and historical experiences. But this immediately raises the question to what extent there is a type of unity in that. If everyone has a particular interest that will make it quite difficult to exchange all of those views and ideas. Or is there still a common framework that makes it easier for everyone to discuss these things with one another? That’s where memorial institutions like remembrance centres and museums play a vital role. I think your initial question can only be answered by saying, that we need to keep on discussing commemoration, not only answering questions individually for ourselves, but having a society wide continuous discussion about the way we think about the past.