Can Social Media Make Commemoration More Inclusive and Diverse?

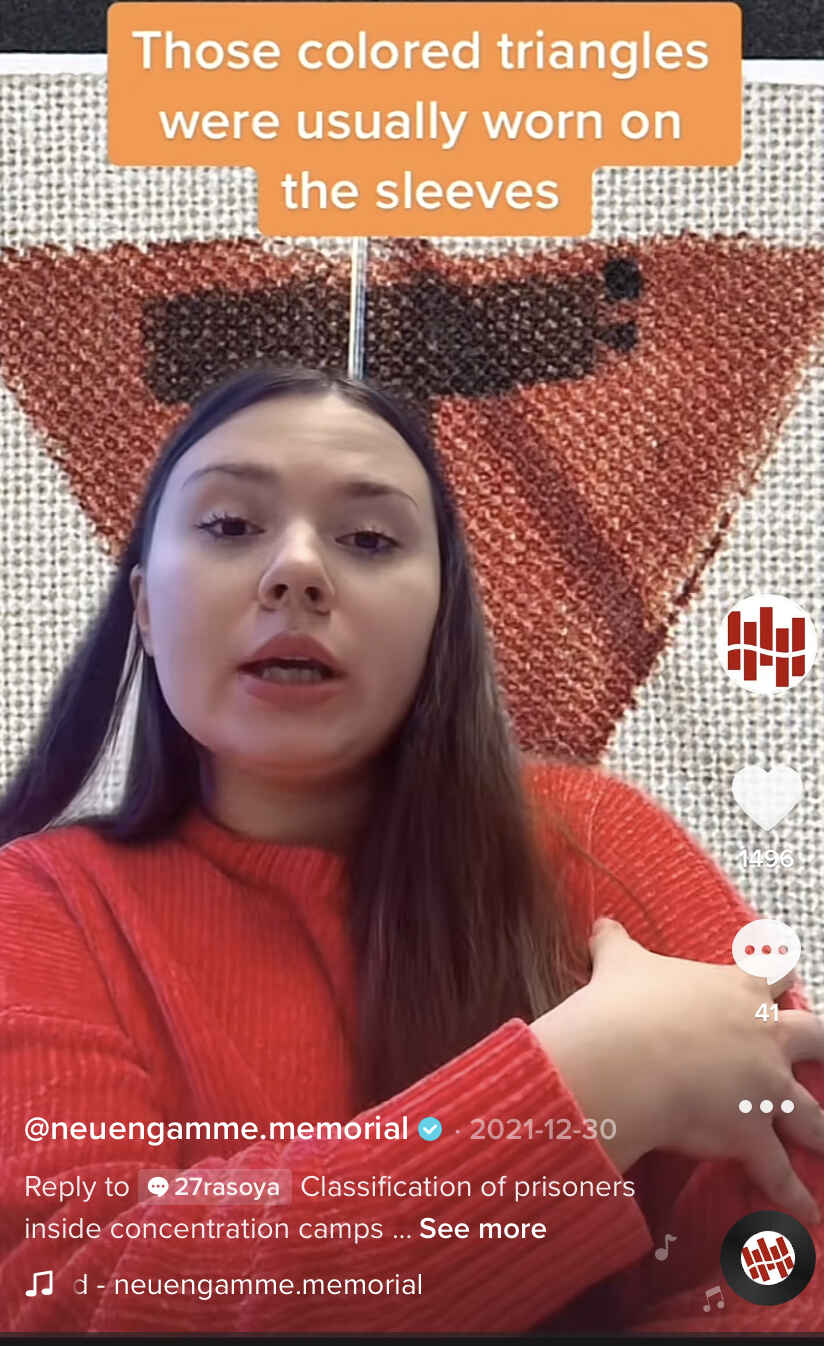

The Neuengamme Concentration Camp was the first institution in Germany using TikTok in order to reach out to a younger audience. Iris Groschek, public relations officer at Neuengamme, is convinced that social media users will shape the way we commemorate.

TikTok and being serious – how does that fit together?

Iris Groschek: TikTok has changed quite a bit in its few years of existence. Initially, the platform has characterised itself as a place for positive entertainment. But if you’re scrolling through, looking at what’s going on, there is much more happening there. It’s not just a self-promotion tool, it’s also a communication tool, that stands for a diversity of topics, and which also functions as a place for political communication.

What amazed me was to hear that TikTok is used as a source of information. Young people, Generation Z, no longer “google” when they want to find out about something, but instead they look at TikTok. I think that illustrates the importance of this platform.

However, we must be aware of the downsides, for example, that this platform can also used as a propaganda tool. If we look at the war against Ukraine, TikTok is not only a place where we are able to perceive a multi-perspective view of a particular event, but a place, where we can also find propaganda.

The special characteristic of this platform is the active community. Being part of this community means actively contributing one’s thoughts and topics. And because of its relevance to a young generation, I think it’s very important to have a presence on there, not only to be simply present, but also to engage in an exchange and jointly develop a digital culture of remembrance for the future.

Serious topics should have a place everywhere, including in the everyday lives of young people. If you are watching short clips in the evening, and a clip of a concentration camp memorial pops up, it’s quite possible that you’ll spark an interest in this serious topic – and people will want to learn more about it. In short, for Generation Z, TikTok has changed from an entertainment to an excellent communication space.

So slowly, more and more institutions and the media are venturing onto the platform.

Absolutely. We want to be visible in the digital world. For example we did a cooperation with Deutsche Welle doing a small series on the concentration camp memorial, and one of the most successful videos of the series is the video of our content creator Daniel. The video is about thoughts on how to behave in a memorial – and got nine million views and more than 3000 comments. Millions of clicks, and going viral, that has never happened to us on any other platform. That’s very TikTok-specific.

How did you decide to use TikTok for your needs and what were the challenges?

We came up with the original idea two years ago. At the time, there was a bit of an outcry on Twitter about victims of the Holocaust being portrayed on TikTok in the form of re-enactments. That raised big questions about appropriateness.

I watched these videos and actually found it very interesting how young people were dealing with the subject matter – in a very different way than it’s usually the norm. They wanted to be part of the culture of remembrance and chose their form of communicating history. I saw it as an opportunity, because an interest in the subject had now evolved on this new platform.

At the same time, the University of Jerusalem took this form of dealing with history as an opportunity to investigate its workings scientifically. With regards to TikTok, they then organized a training course for memorial sites, and we were part of this first initiative. In the process, we dealt with various questions: How does one communicate on TikTok, what works on this platform? Which problems and obstacles could arise for us as an institution? How do we want to present ourselves?

In November 2021, we eventually were the first concentration camp memorial on TikTok – and we were immediately very much noticed and grew quickly on there.

How did you then proceed and use the platform for yourselves?

We set ourselves a few goals right at the beginning. For me, when thinking about using a new Social Media platform, it’s important to start with observation. Which topics are relevant, who is speaking, what sort of language is being used? Only then I consider getting involved as an institution and to start creating. Our goal was to reach a young target group that you we wouldn’t reach in everyday life. On TikTok we have the chance to engage in direct dialogue with this group, at eye level, allowing us to express the relevance of our topics for today’s society. At the same time, we also learn about young people’s thoughts. We also wanted to reach an international community, which is why we launched an English-language channel.

On TikTok, it is very important to have personalisation. So I was very grateful for our volunteers at the time to take that on. We had two ideas for storylines. On the one hand, we shared short clips about the life of volunteers in a memorial, their thoughts, their work and their growing knowledge. And on the other hand, we offered historical information: We presented basic information about the Neuengamme concentration camp for those, who don´t know much about this history, and we also told more in-depth stories, stories that are not as well-known, but very interesting for our target audience, for example about a queer victim.

How do you look at your success on TikTok?

Our account definitely went beyond our initial objective, because we grew quickly compared to other platforms. Compared to our other social media presences, we have by far the most followers on TikTok, by far the most views, the most dialogue, lots of questions and a lot of interest. People have also actually come to visit the memorial, because they’ve seen videos on TikTok. For example, a mother who visited us with her children told us that she had only come, because the children had seen our clips on the net and therefore wanted to visit. I didn’t expect this overlapping of the digital and analogue world. So I was pleased to hear that not only an interest in the subject matter had been generated, but also the interest to come and visit the actual place.

„Institutions are losing a bit of their gatekeeper mentality, because everything is becoming more diverse and open, and memorial culture can actually be co-created, at least online – with a much lower threshold.“

Iris Groschek, Historian at the KZ-Gedenkstätte Neuengamme

The central idea of social media is exchange, interactivity. How do you rate this potential in terms of remembrance culture?

I think on many platforms it’s difficult to actually engage with people. On TikTok, it’s much easier to get into an actual exchange, because there is a certain interest already in the platform itself to be an active part of the communication going on. We see a lot of people do actually comment, asking questions or answer our questions.

It also depends on how I communicate as an institution and whether I ask open questions, so that the community feels invited to get into a dialogue. This way, I also learn a lot as an institution. I think, it’s a real dialogue, because I can take on board thoughts and opinions from the community and the community from me. That’s why I hope that the culture of remembrance will become more diverse and participatory through social media.

On Instagram, there is something similar happening. When I look at the photos of Neuengamme Concentration Camp posted on there by our visitors, I can see, how they present us in their images, what they feel is important to show, and how they ‘construct’ this place – they are just as influential with their pictures as I am. Their pictures shape the way how remembrance sites like ours are seen.

Institutions are losing a bit of their gatekeeper mentality, because everything is becoming more diverse and open, and memorial culture can actually be co-created, at least online – with a much lower threshold.

That’s an interesting idea, that memory culture is also shaped by the actions of users on social media.

If I go back to the beginning of our conversation, to the re-enactments of Holocaust victims on TikTok – the creators had been criticised for that. It was said that the creators weren´t sensitive and respectful enough – but it was not used as an offer to talk to the creators, instead criticising them for their form of storytelling. And in the end the creators learned, that they didn’t have the right to shape memory culture. I thought that this was difficult. All those clips have since been taken down. The University in Jerusalem tracked down some of the creators and interviewed them on the subject. The study showed that they no longer wanted to deal with this topic, which means that they have been lost for this topic. In this case, it would have been better to listen and to engage in conversation instead of blaming these young people for their content. After all, the point of dialogue is openness.

In what ways does remembering National Socialism, for example, change using social media?

There have always been different forms of remembrance, different forms of commemoration. There are still different forms today, in the analogue as well as the digital world. What’s interesting is that the digital realm is able to host new formats quicker, formats that are also accepted differently, while in the analogue realm there are quite often still forms of remembrance that have developed over many decades. In the digital realm, this is all still open – which gives us the chance to create something new. Perhaps also something that interlocks the analogue and the digital. At the moment, in our case at least, we are still dealing with two separate issues.

But this is not only a question of remembrance culture and commemoration, but also of mediation. And there is also another question: What does all of this have to do with us and our present?

We’ve talked a lot about the benefits of social media. What dangers do you see, for example, in reproducing complex content in 60 seconds?

Of course, the Shoah can’t be presented in 60 seconds – I don’t want that and no one could do that.

The big questions you have to ask yourself are: What about trivialization, about reduction, about appropriateness, about being emotionally overwhelming? How can I condense information without inappropriately abbreviating and still cast a multi-perspective view on an event? This is difficult!

We always talk about opportunities and challenges, or rather that these challenges can also be opportunities, because in a TikTok clip I have to focus on the core of the matter, on a particular issue and have come to the point very quick. Even for us, who are professionals in storytelling, this is a new way of thinking. And then there’s the other side of the challenge. Because of course on TikTok, as everywhere else in the online world, there are fake news, there is hate speech, Holocaust denial and Holocaust distortion. You have to learn to deal with that. But precisely because there are so many fake news and misinformation, it’s important that we as an institution are visible as well – we can be a credible, honest voice, at eye level with an interested community.

Would you say you’re also doing a good job countering this misinformation?

Asked differently, what would be the alternative? To stop spreading information, because there is misinformation? That’s precisely why we have to have a presence. Of course, as a place of remembrance, we could also say we focus on being an analogue, a quiet, silent place of remembrance – and of course we are this as well – but at the same time obviously we have a mandate for historical-political education. And I am convinced, this should also happen in the digital world. I think it’s very important to be visible in the digital realm to communicate the relevance of our issues to todays society, not only to the young community, but also to stakeholders and politicians. Institutions need to put even more focus on this and use man- and womanpower to become even more relevant in the digital space. And if professionals are at work, then professional communication can be accomplished.

The last keyword that comes to mind is networking, as we can achieve so much more visibility through campaigns, ‘challenges’ and the like.

How important is it for those shaping remembrance culture not only to use new technologies, but also to understand them and be actually active? Is there still a lot of work to be done?

This is not something that is learned once and then implemented; it is subject to constant change. Take TikTok: It hasn’t even been around that long, but it has an incredible relevance, but in two years’ time it could be over. Besides, what works on one platform does not work on another. You have to constantly keep up with the times and stay informed.

In the days of Corona, however, institutions actually noticed the relevance of digital communication, because there were no more visitors on site. Suddenly, a lot of things had to be moved to the digital realm, and that surprised many institutions as to what was actually possible on there. But there’s still a lot of room for improvement in the form of communication, in the acceptance of the digital; there’s still a lot of work ahead of us. The beauty of this work is that we can work together with an interested community to determine what the culture of remembrance will look like in 20 or 30 years.