Photo: privat

Graduating High School – in Times of War

Even in peaceful times, graduating high school and starting a new chapter in life can be a stressful experience. But how does it feel to be a senior in high school when your country is at war? This is what our author and EUSTORY-alumna Marlene asked her Ukrainian friend Kateryna, who fled to Germany in March 2022 and has lived with Marlene’s family ever since.

The Big “What’s Next?”

My high school graduation in June 2020 is not necessarily a happy memory. Disappointed that prom had gotten canceled due to the Covid-19 lockdown, I felt like the unluckiest person on the planet. On top of that, like many high school seniors worldwide, I felt anxious about the future. Should I go to college? What should I major in? Will I keep in touch with my friends?

However, the war in Ukraine put things into perspective for me. In March 2022, my friend Kateryna and her family, who I have known for many years, had to flee their home country and come to Germany. After moving in with my family, one of the most frequently discussed topics quickly became education. Kateryna was in her final year of high school and asked herself the same big question I had struggled with two years before: “What’s next?”. Becoming a refugee overnight, this question became much harder to answer for her than it had been for me.

A Summer Like no Other

July 2022: I meet with Kateryna and her friends, Polina (16) and Daria (17), in the main pedestrian street of my hometown, a small city located in Western Germany. They sit around a coffee table, chatting and eating ice cream. Nothing unusual for this time of the year – it is the second week of summer break, and many teenagers are out roaming the streets. But as Ukrainians, their summer is anything but ordinary. “Today, it’s been exactly four months since I arrived in Germany,” Kateryna says thoughtfully, gazing at the floor. She speaks slowly, like she is struggling to wrap her mind around this fact. One could call this day a mini anniversary for her, none to be celebrated, though.

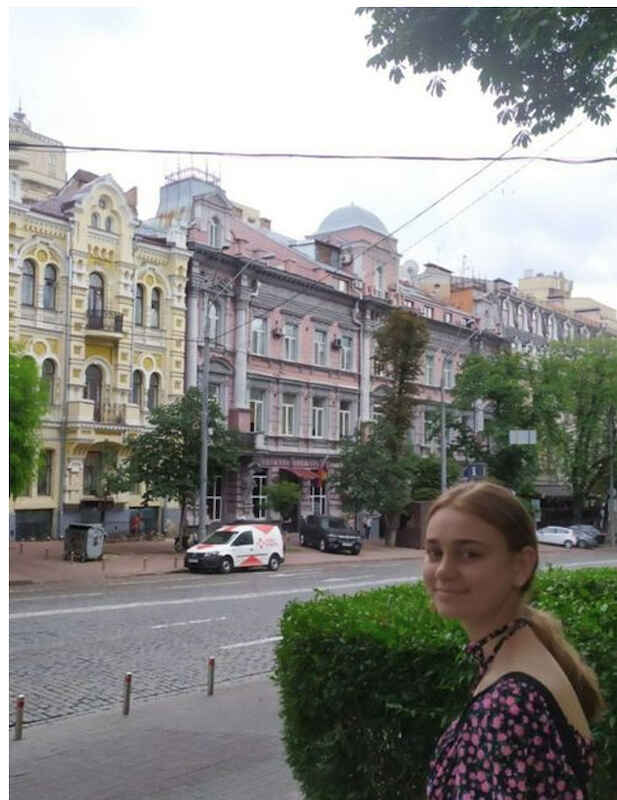

Leaving Lviv, Keeping The Memories

Kateryna’s hometown, Lviv, is a big city in Western Ukraine famous for its Austrian-Hungarian heritage among tourists. Since war broke out, the city has become a hotspot for internal refugees from Eastern oblasts. Before, the town was known as the pro-Western stronghold of the country, with an overwhelming majority of the population speaking Ukrainian. Unlike many other regions where Russian is the dominant language of everyday life, in Lviv most people spoke Ukrainian even under Soviet rule. In Lviv, Kateryna lived a typical teenager’s life. “I had lots of different hobbies, went to dancing classes, had archery lessons, and played piano at a music school for eight years,” she says. Although the last two years under the pandemic were quieter, she liked wandering downtown streets with her friends, admiring the gorgeous architecture. “Looking back, it truly was the best time of my life,” Kateryna says with nostalgia in her voice.

School From Bomb Shelters

“In February, I was still certain to graduate this summer and start college in Ukraine,” Kateryna remembers, spinning her ice cream spoon between two fingers. Visibly disappointed, she adds: “My classmates and I would have been the first year after Covid lockdown to have a traditional graduation ceremony and prom again.” When the war started, schools nationwide closed for two weeks until the department of education had devised a plan. By the time schools opened again, approximately one-third of Kateryna’s class had scattered all over Europe: Poland, Germany, England, and many more countries. Despite many difficulties, her school continued to have online lessons. Some lasted only 15 minutes, interrupted by the ear-piercing sound of air alarms and teachers running to bomb shelters.

Not a Vacation

In March 2022, her family decided to leave Lviv days after the war had started, convinced they would be back in a week or two. “This will almost be like a vacation,” Kateryna had told herself as she, her mother, and younger sister got on a bus to Warsaw. After all she had wanted to visit her friends in Germany anyway. But their trip did not resemble a vacation in the slightest. It took them a whole day to make it to Poland’s capital, usually just a six-hour drive. The endless line of cars waiting to cross the Ukrainian-Polish border slowed them down tremendously. In addition to that, their bus was not only hopelessly overcrowded with children, mothers, and the elderly. But some had also taken their cats and dogs, which made the ride the opposite of comfortable.

When the family finally arrived in Germany by train after more than a week on the road, Kateryna still expected to be back home in no time. Germany was supposed to be a short intermezzo of her everyday life. Even after the first couple weeks, she still hoped to celebrate Easter with her dad, grandparents, and the family puppy in Lviv. But “just a few weeks” quickly turned into four months.

Kateryna in front of Abendrealschule in fall 2022 Photo: privat

Polina, Daria, Kateryna discussing their plans for the future at an ice cream café downtown, July 2022 Photo: privat

Memories from peaceful times: Kateryna and her older sister in Lviv’s downtown, August 2019 Photo: privat

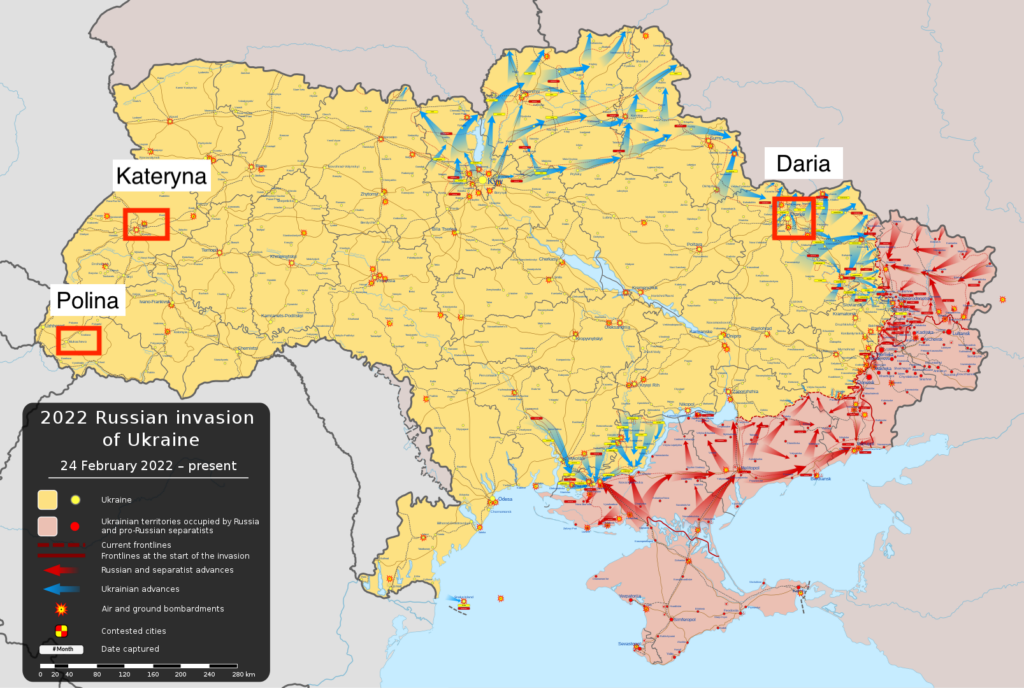

Daria in her hometown, Kharkiv, before the war Photo: privat

Under Damocles’ Sword

Despite some fun memories, there is a daily reminder why she had to come to Germany. The daily news sometimes makes it hard to carry on for Kateryna. Stories about distant relatives and acquaintances being wounded or killed in the war arrive regularly. Her life in Germany is a somewhat strange mixture of immersing herself in a new culture and simultaneously remembering the horrible reason she had to come here. Defying the never-ending stream of discouraging war news has become a daily task.

Juggling Two Schools

Since February a lot has changed in Kateryna’s life. Until the war, she had visited the 11th grade – in Ukraine the final year of secondary school. Now the 17-year-old attends “Abendrealschule,” a German high school designed for international students like her who are too old to fit into the traditional German school system. The main goal here is not to study Math or other subjects but to learn German as fast as possible. School has given her a new routine that keeps her busy almost the whole day: In the morning, she goes to her German school, while afternoons are for Ukrainian school and additional tutor classes, she is taking to prepare for NMT, the university entrance exam in August.

Soul Places

Despite going to two different schools, there is still enough free time to discover her new “home.” She likes the amount of nature surrounding the small town. “In Lviv, I always dreamed of having a river nearby. Here we even have a little creek in our back yard”, she says, excited. Her “soul place,” as she calls it, is a small café in the middle of the woods next to an old monastery where she and her new friends have picnics on sunny days. She also enjoys cycling and working out at the gym. “I was shocked that they have only communal showers there. You don’t find that in Ukraine,” she laughs. “But I think I would be more active if I had had more local friends.” For now, most of her friends are Ukrainians from school.

One School, Different Stories

At her new school, Kateryna met Polina and Daria, who attended the same exclusively Ukrainian class. Their stories and plans differ despite sharing one culture and living in the same new place under similar circumstances. Kateryna and Polina both come from regions in Western Ukraine that – with a few scary exceptions – have not been a primary target of the Russian military. Nevertheless, air alarms, sporadic missile attacks, and the destruction of critical infrastructure have made life unpredictable and a psychological challenge. Yet, there is still an “old life” to return to one day. In contrast, for Daria and many other students from Eastern oblasts, leaving home was not temporary. Like most buildings in Kharkiv, Daria’s home was destroyed by a Russian missile in spring when her family already stayed in Germany. For months there have been missile attacks on the city almost every day, killing countless civilians.

Old Dreams, New Opportunities

Once in Germany, she did not even bother preparing for NMT anymore, Polina says. She had always dreamed about studying abroad, initially in the Czech Republic, where her older brother goes to college. “But now I would like to study in Germany, preferably biomechanics,” she says. Since high school for college candidates lasts one to two years longer in Germany than in Ukraine, there is still lots of time left for the 16-year-old. Time, she uses to bring her language skills to perfection.

Lessons From Covid

Unlike Polina, 17-year-old Daria would like to return home to Kharkiv. When and how? – no one knows. Despite brutal fighting back home, her plan to enroll at Kharkiv university had to be only slightly adjusted. Thanks to Covid-19, the university is familiar with online and hybrid classes, enabling Ukrainian refugees abroad to continue their studies. Online college is something Kateryna considers, too. Of course, she would prefer to study in person and experience real college life. But this would only be possible in her hometown Lviv, a relatively safe city right now.

When College Can be Deadly

College applications are a big part of Kateryna’s day. For months she has looked at different universities in Ukraine and abroad, trying to find the best match for her. But unlike others, the number of offered classes or campus life is not her main criterion. Before all, she considers the risk of missile attacks and the proximity to the front, aspects she never thought she would have to think of when choosing a college. Unfortunately, despite having high scores at NMT, there is no guarantee of getting accepted at Lviv’s university. Alternatives like Kyiv or Kharkiv? Far too dangerous in person. Enrolling at a German college would also be possible for her. But being a minor and speaking only a little German, this is not something she seriously considers – as is going to college abroad. This would mean leaving Ukraine permanently for the next couple of years, the opposite of what she wants.

The Privilege of Comfort Zones

When I graduated in 2020, as a German citizen, I had the freedom to choose whatever college I liked solely based on my preferences. I took it for granted that I was able to make the conscious, voluntary decision to stay with my family and not move out of my home. Had I opted to go to university far away, my family would continue their lives as usual, and I could return home any second.

Kateryna, Polina, and Daria no longer have this security in life. Although their families are alive and safe, they have (at least temporarily) lost their homes as a secure base and learned that sometimes your worst nightmare comes true. The obstacles in their way were undoubtedly more significant than those of the average college applicant. But despite being confronted with daily horror news, a new culture, and personal losses, they managed to navigate everyday life and make responsible choices for their future. Graduating high school and becoming an adult is about leaving your comfort zone, some people like to say. For very few people in Europe (or the world), this statement is more accurate than for Kateryna and her friends.