Photo: Anastasia/Körber-Stiftung, FES, ZOiS

A collapse with consequences: On December 8, 1991, the Soviet Union officially dissolved. The largest socialist state, which for almost seven decades encompassed what is now Russia, Belarus, Moldova, Ukraine, the Caucasus and the republics in the Baltic States and Central Asia, was no longer able to maintain its power.

Thirty years later, the long-term impacts of the disintegration are still visible and tangible: They show up on the political map and in the power structure of world politics – but also in the everyday life of a post-Soviet and post-socialist generation that did not experience this period personally.

19 people aged between 18 and 24 from 13 post-socialist and post-Soviet countries document how the past still affects the everyday lives of the young generation today: As part of the digital programme “#30PostSovietYears: Phantom Pasts or Everyday Present?”, they searched for traces in their hometowns and captured the interplay of past and present with their cameras.

A project in cooperation with Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung Moscow (FES) and the Centre for East European and International Studies (ZOiS).

Daily Companions

Mariia, 21, from Russia/Moscow

For Mariia understanding the Soviet past means decoding the imprints and values of her relatives who grew up in the USSR.

As part of the programme, she focuses on the objects and places that accompany her every day: A glass whose patterning reflects the 16 Soviet republics, a workspace in the university, the entrance area of the Russian State Library, and a café where Soviet dictator Josef Stalin adorns the wall next to Che Guevara. The omnipresence of the Soviet past provides Mariia with some explanations for the present.

Photo: Mariia/Körber-Stiftung, FES, ZOiS

Photo: Mariia/Körber-Stiftung, FES, ZOiS

Photo: Mariia/Körber-Stiftung, FES, ZOiS

Photo: Mariia/Körber-Stiftung, FES, ZOiS

Search for Identity

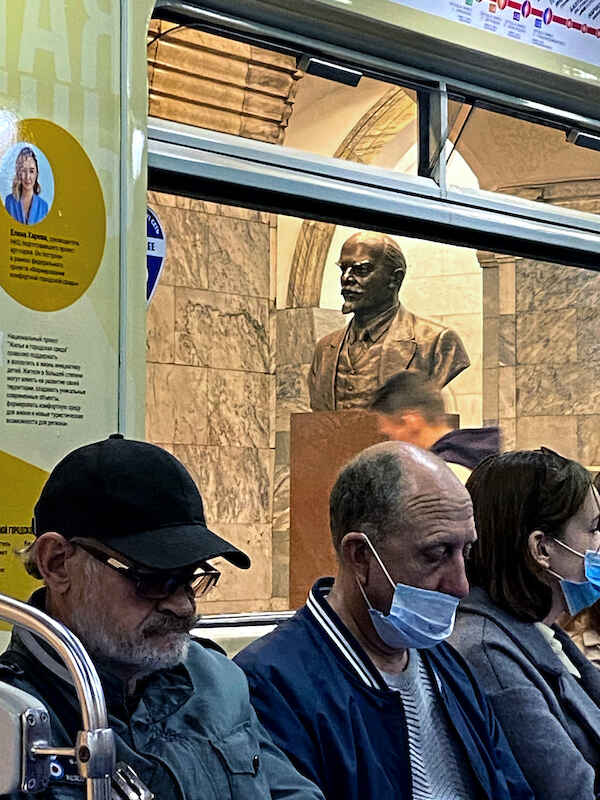

Anastasia, 20, from Russia/St. Petersburg

“Am I as Soviet as my grandma, despite the fact that I was born when the USSR was already 9 years out of existence? I don't know.“

For as long as she can remember, Anastasia has been trying to understand developments in her country – and thus her own origins and roots. The legacies of the Soviet and socialist systems still have an enormous impact on the public sphere, but also on her private space: Josef Stalin in particular, but also other key Soviet figures adored as national heroes, are encountered anew every day in her everyday life – and give her an idea of the significance of the past for her present.

Photo: Anastasia/Körber-Stiftung, FES, ZOiS

Photo: Anastasia/Körber-Stiftung, FES, ZOiS

Photo: Anastasia/Körber-Stiftung, FES, ZOiS

Photo: Anastasia/Körber-Stiftung, FES, ZOiS

Architectural Traces

Petar, 23, from Serbia/Belgrade

Petar explores and captures old, abandoned buildings and areas in his city. Many architectural traces date back to the time of socialism, which increasingly took on a special form in Yugoslavia from the late 1960s onwards.

For Petar, those relics of the past also have a personal meaning: The Yugoslav Western-oriented foreign policy, initiated by Josip Tito who is still considered a national hero by the older generation, made it possible for Petar's grandparents to get to know each other. For Petar, their Pfaff sewing machine from Germany still symbolizes the coexistence of East and West – in the former Yugoslavia as well as within his own family.

Photo: Petar/Körber-Stiftung, FES, ZOiS

Photo: Petar/Körber-Stiftung, FES, ZOiS

Photo: Petar/Körber-Stiftung, FES, ZOiS

Photo: Petar/Körber-Stiftung, FES, ZOiS

Divided City

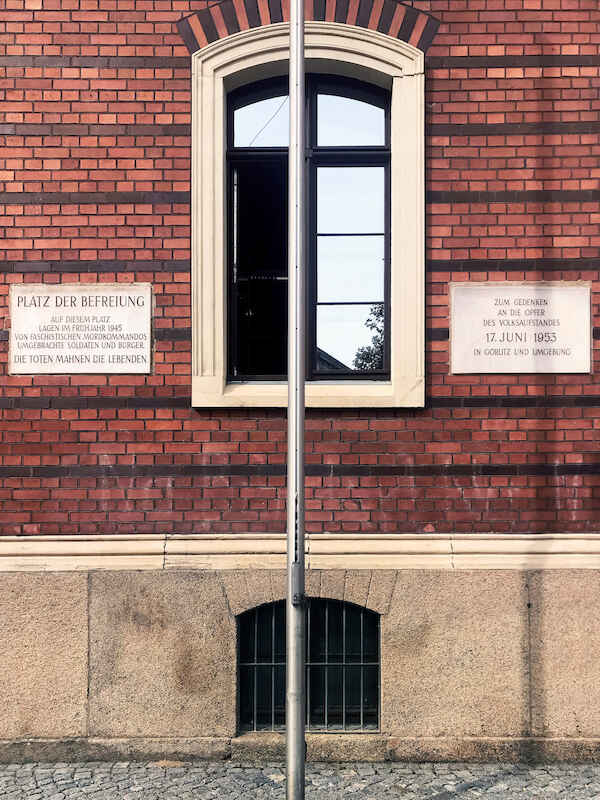

Hanna, 20, raised near Görlitz

“As a divided twin city, history has shaped my hometown a lot.”

Hanna was raised near Görlitz, the most eastern city in Germany. After the Second World War, Görlitz was part of the Soviet occupation zone. Due to Poland's westward shift, the city was henceforth separated by the Lausitzer Neisse River into a German and a Polish part.

Today, a pedestrian bridge connects the Polish and German sides – unlike in the days of the GDR, when it was not easy to cross over to the “socialist brother state” Poland.

Photo: Hanna/Körber-Stiftung, FES, ZOiS

Photo: Hanna/Körber-Stiftung, FES, ZOiS

Photo: Hanna/Körber-Stiftung, FES, ZOiS

Photo: Hanna/Körber-Stiftung, FES, ZOiS