XR-History Award 2024

Historians and their books have long dominated most visible spheres of historytelling and commemoration. Digital tools are some of the instruments that allow us to challenge narratives, bring previously unheard voices to the forefront of historical remembrance and expand opportunities of collective memories.

This year we looked for a creative XR project that skilfully combines elements of narration, art and history to achieve a critical reflection on historic discourses and memory.

We have a winner!

We are delighted to announce: the XR-History Award 2024 goes to: Loot. 10 Stories by Jongsma + O’Neill!

Loot.10 stories is an immersive exhibition that uses VR, documentary and installation design to investigate the problem of looted art in museum collections, and to examine the potential steps—be they legal, technological or personal — that can be taken to address historical injustices. The project uses human-scaled storytelling to emphasize and spotlight the subjective perspectives of the people and communities who have been impacted by the taking and exhibiting of looted art.

Originally designed for the Mauritshuis in The Hague, Loot. 10 Stories has since captivated audiences at the Humboldt Forum, Berlin, where it can be seen until January 2025.

Jury member Esther Wright summarises: “This project offers a new way of asking the public to consider the status of looted objects in museums, openly reflecting ongoing conversations about this issue and facilitating a different take on the kind of “commemoration” that such institutions traditionally offer. There’s a nuanced contrast between the physical and digital, and past and present here: between the objects, their origin, current location, and how they arrived there. Underpinning this, the use of XR tools have a specific purpose in the experience, rather than being employed for novelty. Different aspects of the installation take visitors to a different context to help them understand an object’s complex history.”

The XR-History Festival 2024

Immersive media change and expand our ideas and interpretations of space and time and thus also the axes through which we construct and interpret history. With the XR-History Festival on 6 June 2024 at Deichtorhallen, we celebrated the diversity of memory culture and showed how we can discuss and establish a better present and future via digital history-telling. The XR-History Festival, created by the eCommemoration programme of Körber Stiftung is unique and the only festival of its kind.

Moderator Nhi Le accompanied us through the evening as host and interviewed our guests on her couch on stage. This year’s XR-History Award winner, Jongsma + O’Neill , were also there to talk about their project Loot. 10 Stories. Our visitors were invited to explore ten different XR-playgrounds, join guided tours through Deichtorhallen’s exhibition „Survival in the 21st Century“ and listen to the musical programme presented in collaboration with PAL TV: a live set by Zoe Mc Pherson (SFX).

Our guestlist included Mareike Ottrand, Simon Denny, Thorsten Logge and Nadine Isabell Henrich. The exhibited projects were: #MakeUsVisible by the eCommemoration programme, Kinfolk, Child of Empire(Winner of the XR-History Award 2022), The Post-Truth Museum by Nora Al-Badri, Memoria: Stories of La Garma, Subterranean Imprint Archive, Nepenthe, Fãl Project and Kampnagel’s Decolonial Gaze.

Our Guests

A Blueprint For The Transformation of Museums

In Loot. 10 Stories, film-makers Eline Jongsma and Kel O’Neill have investigated ten objects looted at various points in history — by Napoleon in Berlin, by Nazi Germany and during the Dutch colonial era. In this interview, the winners of the XR History Award 2024 talk about the digitalisation of the museum world and why their project could be a blueprint for transformation.

The discussion about looted artefacts and cultural heritage has been going on for a few years now. And it is quite controversial. Why do we have to tell stories of looted art now?

Kel O’Neill: These conversations are happening behind closed doors in the museum context, in the governmental context, but they’re not necessarily happening between people who are directly affected by issues of looting and restitution. Our job, in a lot of ways, was to surface this conversation in a way that was inclusive and brought in people from outside of the sectors in which these debates are siloed generally. We’re just bringing people to the table, more than we’re bringing up some grand new idea that isn’t being discussed by anybody.

Eline Jongsma: We were interested in looking in the depots of museums in Europe, specifically to get access to objects that were deemed impossible to exhibit for whatever reason. We wanted to see if there was a possibility in a digital manifestation of this object, that it suddenly would become possible to exhibit them. This was what we were researching independently, before we met up with the director of the Mauritshuis, Martine Gosselink, who has been working on restitution efforts in her various jobs and positions throughout the years. We asked her: Do you have anything in your depot that you and your curators think is impossible to exhibit? We are aware that the depots, specifically in Europe, are full of amazing treasures, stolen and not stolen. And these treasures are unexplored for general audiences.

Stiftung Humboldt Forum im Berliner Schloss / Mauritshuis in Den Haag, Jongsma + O'Neill / Photo: Alexander Schippel

Stiftung Humboldt Forum im Berliner Schloss / Mauritshuis in Den Haag, Jongsma + O'Neill / Photo: Alexander Schippel

Stiftung Humboldt Forum im Berliner Schloss / Mauritshuis in Den Haag, Jongsma + O'Neill / Photo: Alexander Schippel

Loot. 10 Stories is using VR technology. What role does and can digitalization play in restitution debates?

Jongsma: In a lot of ways we are already living only in a digital space. We all are married to our smartphones. This process of slowly living in a digital world more and more is happening very gradually. It’s like a slow boiling frog. We don’t know that we’re already so far in that direction. For us as makers, it’s always interesting to see the new territories. Where can we take these questions about digitalization and the future of media? I think the museum space is hopelessly antiquated, pun intended. While museums are trying to figure out, should we restitute or should we not, what do we do, we kind of swooped in and said, here you go. This is how far we already are.

O’Neill: It’s like in the academic and museum realms, the first instinct is to problematize, discuss and come up with best practices. And that process takes more time than we have. While we were finishing, this YouTuber who I know put up some video of himself going to the Uffizi in Florence and making a Gaussians splat of some priceless objects without the guards catching him. And then he published in this video exactly how to do it. The presence of that video, the presence of this information in the mainstream, is hundreds of kilometers ahead of the debate on whether digital doubles need to have some kind of legal clearance in order to be displayed. We have a clear code of ethics in how we employ the digitized objects. Permissions were granted and disclosures we made along the way. But that YouTuber didn’t think about that for a moment. With it going this quickly, it’s up to museums to acknowledge that and start moving in the direction that people are moving in.

When we talk about digitalization in this context, we also need to talk about copyrights or the intrinsic value of the objects.

O’Neill: Of course! Individual scans of the objects that exist have been discussed with the museums, with representatives of the communities. We had a lot of discussions that were big tent discussions. Ultimately, it comes down to the question of whether a digital object is a real object and has to be looked at through the same lens. And this is a debate that’s going to be going on for a long time with many different sides in many cases. It’s not something that we can resolve with one exhibition, but it is something that we can raise. And we bring people to the discussion who may not normally be in the discussion, so that there’s a multiplicity of voices and not just people in the sector discussing.

Jongsma and O’Neill wanted to do things differently. They went to Bali to research a knife that you can see in the exhibition, and asked the King of Klungkung if he was interested in having it returned. He was not. Later, in an unrelated report that they read in the paper, we found out that his family requested the return of another knife. These experiences are also portrayed in the show.

“I think, especially with restitution and trying to create more equal societies or a just world, you have to embrace subjectivity as a museum and accept that there are many perspectives. Thus, there are many perspectives on an object, there are many stories, there isn’t just this Western perspective that you can take.“

Eline Jongsma

How will digitalization transform how museums show their exhibitions? More specifically, what will happen once museums have to give back all their looted artefacts?

Jongsma: The problem is that you have to label every object either stolen or not stolen, which is an impossible task. Specifically with stolen objects, the provenance is not clear. You often cannot prove what the history of the stolen objects is. And then there is this giant group of objects that were maybe bought, but bought under suspect relationships. There’s a whole bunch of objects that maybe aren’t technically stolen, but you could argue that they are. That’s a really hard thing to do that you have to figure out before you start bringing real process into your museum, where do you start giving things back. There’s the relationship between digital spaces and physical spaces that needs to be examined more. Not in terms of which one is worth more, but how do we relate? The Humboldt Forum in Berlin is a very large museum. There’s a lot of space there that is not being utilized. And I don’t think that that’s going to change because we have all these digital alternatives to going to museum spaces. It’s a tough time for museums. They’re competing with a lot of different types of entertainment. I personally believe that you have to move in the same direction as society, and not create a counter movement. Maybe museums are not going to be temples that show objects in the future.

O’Neill: Our show is a direct response to your question. It includes a series of test cases that show what the museum’s role could be once a digital layer is integrated. But I don’t just mean VR, but the videos. I even would go so far as to showcase some of the non-digital elements, for instance, the Benin bronze copies. It is very much a museum show, it’s a show that happens in a museum. But the objects aren’t necessarily central to every test case that’s presented to the visitor. And so far the visitors have embraced it. And I think that is a good signal for museums that they don’t have to stick with doing things the way that they’re doing. There are alternatives to the status quo.

Jongsma: Also, we have to embrace the subjectivity that people like us bring in. Because I think that traditionally the idea is that the museum is there to educate us and that there is one truth that we’re being taught. But I think, especially with restitution and trying to create more equal societies or a just world, you have to embrace subjectivity as a museum and accept that there are many perspectives. Thus, there are many perspectives on an object, there are many stories, there isn’t just this Western perspective that you can take. The voice shouldn’t be didactic. I think that people don’t really want that in the future anymore.

Why did you choose VR technology for your purpose and not, for instance, AR?

O’Neill: It is also AR. The way that the digital world sits over the physical world is AR because they map onto each other. It is altering the reality and augmenting the reality of the visitors, because they see an object in a physical space, then they see an object in the same position in a digital space that overlays the exhibition. And then they return to the exhibition while having their perspective augmented. We’re very conscious of the fact that even though it is VR on some fundamental level, it also is AR.

Jongsma: I also think that storytelling capabilities of AR are still more unexplored than VR. But we are very interested in pushing the storytelling boundaries in that medium. Another reason why AR in Loot is very light, is because we try to make an exhibition where the technology doesn’t scare people. I want a seamless experience and see if that’s possible. This is made for all audiences. That’s also why we have three levels of virtual reality experiences. You can sit in one experience, you can hold on to a railing in another and in a third you really walk around. This is very consciously designed.

The VR stories in the show transport the visitor back to the time when certain objects on display were stolen. These short experiences act as time machines, briefly kicking the museum goer out of the museum context, and encouraging them to contemplate the full past (and potential future) of these objects that ordinarily, when viewed in a vitrine in a museum, could easily be seen merely as “museum objects.”

Mauritshuis in Den Haag, Jongsma + O'Neill

Mauritshuis in Den Haag, Jongsma + O'Neill

Mauritshuis in Den Haag, Jongsma + O'Neill

How did the idea for Loot. 10 Stories come about in the first place?

O’Neill: It was a snowball effect. First we went to the Mauritshuis with the what is impossible to exhibit concept. Martine called us that she wants to make something about looted art in the broadest possible terms. Then we pitched it to the Humboldt Forum, including the Stadtmuseum and the Ethnology Museum. Over time we just saw our interest in the subjects grow and our responsibilities around the exhibition grow. Oftentimes you don’t have the time or budgets to discover what you’re making while you’re making it. And in this case, things aligned in such a way that we took that opportunity.

Jongsma: There was a long development period. Most of the work that we do has an element of looking at how history is surfacing in the present. The topic and the way we created the stories is very much like the way we always work. The jump to go to create something in Bali, for example, around one of the stolen objects, a knife was a logical step for us. We want to involve people who normally aren’t part of the conversation. This is all inherent to our methods.

Creating VR exhibitions is complex and expensive. How did your partner museums react to that? How did you handle this process?

Jongsma: Martine Gosselink is a real champion in this exhibition. She really carried it. The finances obviously didn’t come out of our pockets. As a creative team, we are like this little spaceship that has to attach itself to a larger ship temporarily. And then you have to figure out a way to work together. I think that overall it hasn’t always been easy to convince people in the museum sector to understand the importance of doing this exhibition this way. That was definitely an uphill battle.

O’Neill: You have to give people language that they can understand. Once we started saying things like this is an intervention?, then there was common language. If I were in the museum world and these artists came out of nowhere and decided that their job was suddenly to critique everything about what I believe in and what I do, I would be defensive as well. Once we made it clear that we were intervening in this space and that we could also be used as a shield, it was good. If there was going to be critique, it wouldn’t come down on the institution, it would come down on us.

“We didn’t want to use the categorizing that museums traditionally have done and still do.”

Eline Jongsma

With Loot you tell ten different stories from different epochs. Why did you decide to choose from various periods of time?

Jongsma: It is a collaboration effort between different institutions. And the selection of the objects was a joint effort. These three time periods, that objects were chosen from, are all time periods that affect most European nations. This show was not just made for the Netherlands or Germany, we’ve made this show to appeal to an international audience. That makes it very legitimate to bring these objects together in one space. It’s not necessarily about how they relate to each other or that these objects are somehow the only representation of these issues, it’s more that we are taking objects from time periods that have a real significance to Europe.

O’Neill: A lot of these objects are only thought of as being from that time period because that’s the way that they’ve been labeled within the museum context. But there are intersectional histories going on in this space. Take the head of the Quadriga of the Brandenburger Tor. It is a Napoleonic object because he stole it. But it is also a World War Two object, because it was remade after Berlin was bombed.

Jongsma: We didn’t want to use the categorizing that museums traditionally have done and still do. They have a neat systemising and categorizing of objects: This is a religious object, this is an art object, this is an ethnographic object. We have the freedom as filmmakers and artists to not make those distinctions.

O’Neill: To give you one example from our show: Onias Landveld was brought to the Humboldt Forum, and he looked at and held an object that is categorized as ethnographic. But the first thing that he says when he holds it is: This is how my people made art. All of those discussions about how to label those objects go out the window the minute that a new perspective comes out.

Did you have a certain goal you wanted to achieve with this specific show?

Jongsma: Because we work as documentary filmmakers, I think we always have this goal to uncover and lay bare something that is hard to look at. There’s honesty in that. At the same time, we embrace subjectivity because things are difficult to talk about. If you take subjective perspectives, it somehow makes it easier for people to accept. If we don’t have to have the overarching consensus about how we all think we should think about it. We as makers, as filmmakers, as artists, we don’t. It’s never objective from the start. I do want a lot of openness in terms of what conclusions people draw themselves, because I don’t think that people really want to be told what to do. It’s more about planting seeds.

How was the audience response so far?

Jongsma: There was something that the Mauritshuis added to the show, when visitors exited the exhibition hall, they could draw on a board their response to they what they think the future of these objects should be. When they proposed this, we were a little bit afraid, people are just going to draw stupid stuff. But the contrary was true. It was so fun to read people’s responses because they were so engaged. One thing that I’ve heard a lot, that somehow the exhibition really activated people to think about these issues.

O’Neill: We’re talking about tens of thousands of people in both locations so far. That’s very important data to us because it also shows that the investment is worth it. And it shows that on a certain level, an exhibition like this can stand toe to toe with a film. It very handily sidesteps the technology issues that go with virtual reality most of the time, because everybody knows how a museum works. This is a test case. It’s a proof of concept, that a show like this can work in a museum context and people will show up.

The exhibition drew more than 35,000 visitors during its 3.5 months run at The Mauritshuis in the Netherlands. Internal studies initiated by The Mauritshuis indicate it attracted a younger and more diverse audience than is typical of the museum. In December 2023, in an address to the National Museum Congress, then Dutch Minister of Culture Gunay Uslu called Loot- 10 stories the most innovative exhibition of the year.

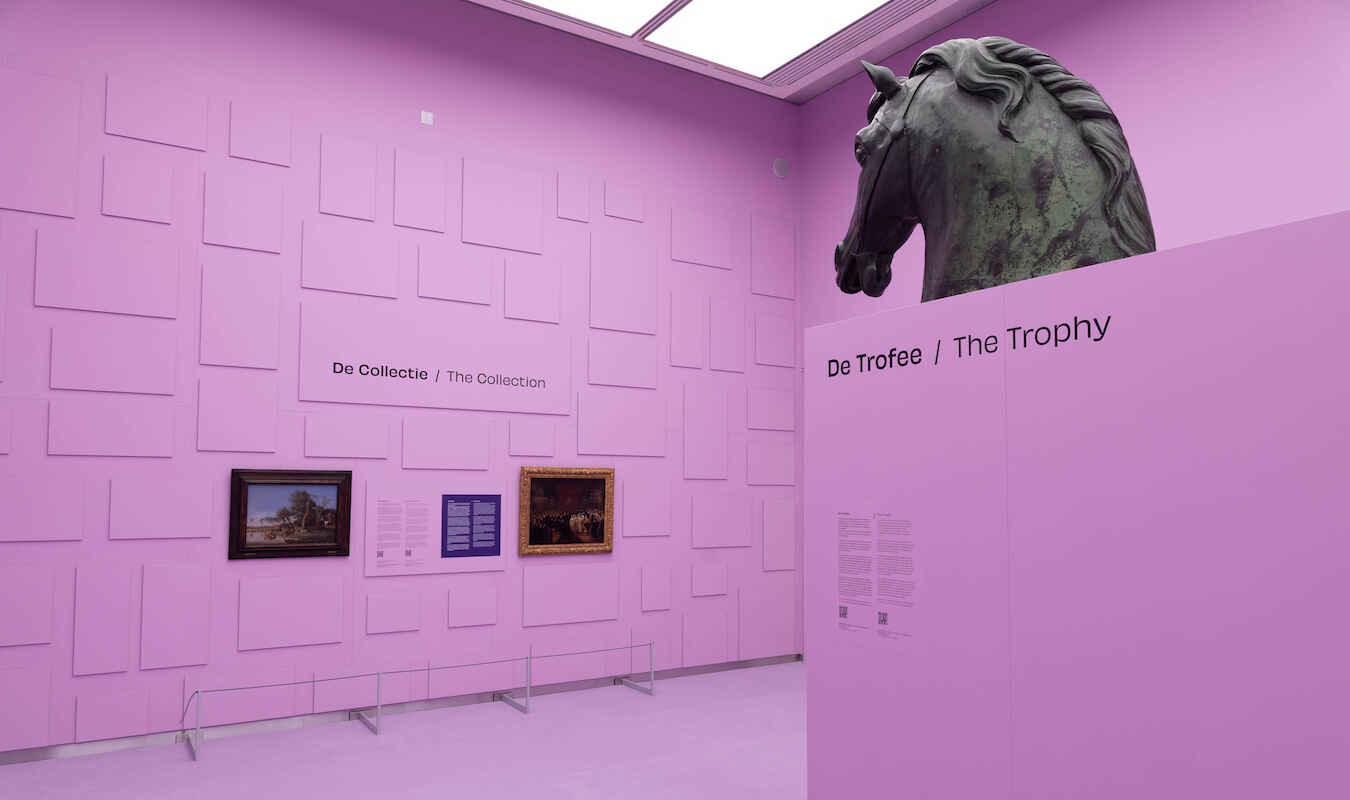

The exhibition is currently on show at the Humboldt Forum in Berlin. The team created a jewel-box concept in which the VR elements are contained within a larger, aubergine-coloured box structure – digital lavender is the name of the colour, that is „supposed to transition you into that space that is neither digital nor real life“, says Jongsma. „Once you’re in between, you’re in an elevated space.“

XR-History Award Shortlist

visuals from Newviewing 43, curated by Mukenge/Schellhammer, Barbara Thumm Gallery

Our Jury

The XR-History Award is a biennial award initiated by Körber Stiftung’s eCommemoration programme, honouring projects using immersive technology to explore artistic approaches of history-telling, history education or commemorative culture.

First awarded in June 2022 in collaboration with VRHAM! Virtual Reality & Arts Festival, it is currently the only digital arts award, which explicitly addresses and encompasses digital projects that interweave past, present and future.