Photo: Alexey Demidov/Pexels

Exile Visual Arts Award

The Exile Visual Arts Award honours works by artists with exile experience that visualise essential questions such as identity, belonging or foreignness. The 10,000 euro prize is an initiative of the Körber Stiftung, supported by the Stiftung Exilmuseum Berlin.

Call for Entries

Exile Visual Arts Award: Call for Entries

About the Exile Visual Arts Award

Freedom of art and artistic expression are fundamental rights in democratic societies. If these rights are abrogated and artists are persecuted, they are forced to flee and seek refuge in exile. The experiences of persecution, flight and exile can find artistic expression in very different forms.

The Exile Visual Arts Award honours works that deal with the country of origin, flight, expulsion and exile in the visual arts and convey unusual perspectives on essential questions such as identity, conflict, belonging, community, individuality, foreignness, attributions, injuries, ruptures or transitions.

Eligible works include visual arts such as painting, graphic art, drawing, sculpture, installation art, photography and new media. The prize is aimed at individual artists with experience of exile who are mainly based in German-speaking countries of exile (Germany, Austria, Switzerland).

The next application period online is from 1 July to 15 August 2024.

A jury of renowned representatives from academia, culture and society determines the award recipient. The winner will be announced in autumn 2024.

Exile Visual Arts Award 2023

Award winner

The Exile Visual Arts Award 2023 went to the Iranian artist Farkhondeh Shahroudi for the works ‘Sky is no one’s ground’ and ‘Max Beckmann was not here’. The award ceremony took place on 8 September 2023 as part of the opening of the Days of Exile at the Berlin Academy of Arts.

Farkhondeh Shahroudi has lived in exile in Germany since 1990. Much of her work reflects her artistic engagement with revolution, war and flight. This also applies to the two award-winning works:

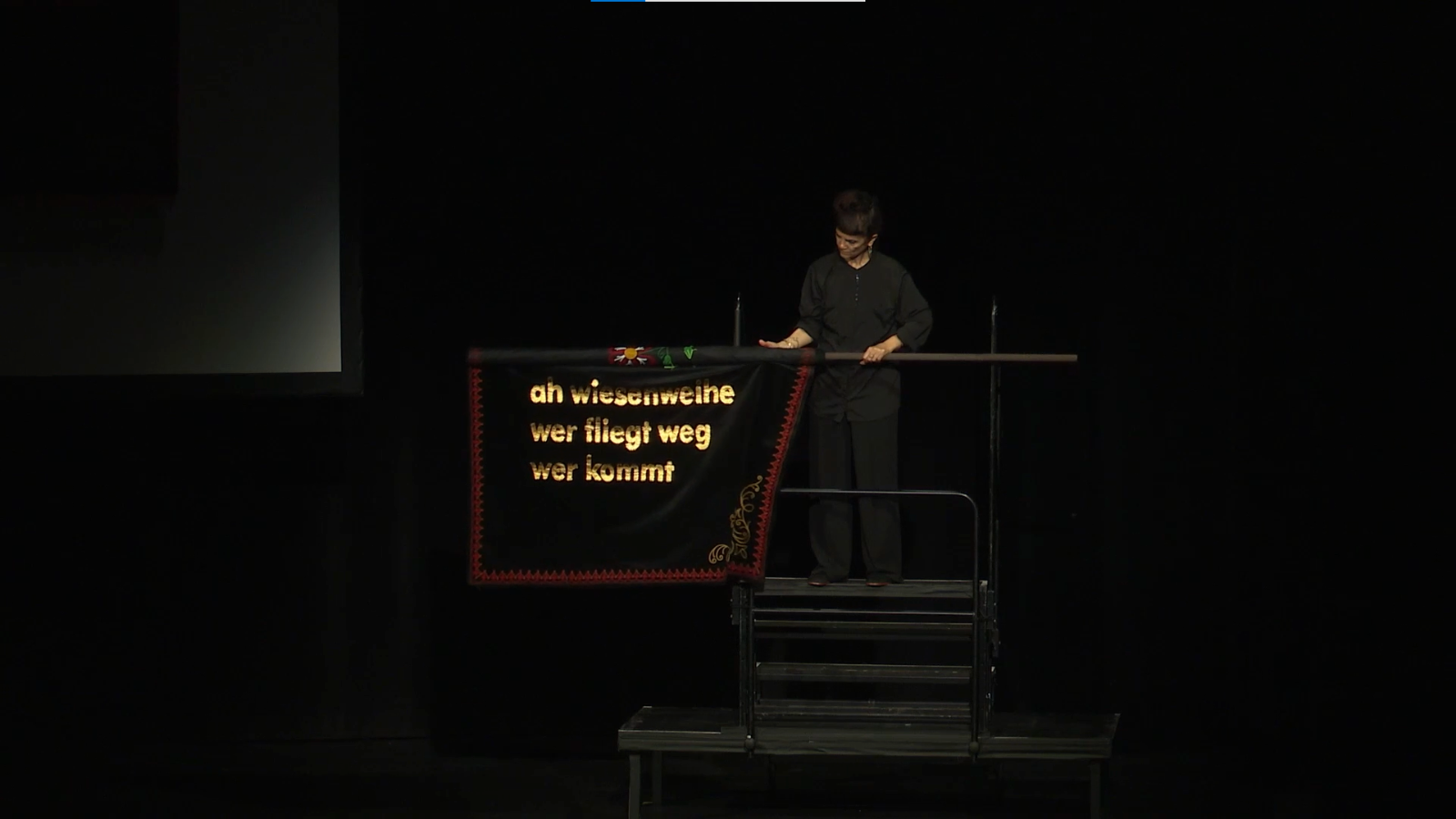

The work ‘Sky is no one’s ground’ (2019) consists of a flag with appliqués and embroidery on velvet. As part of a performance, the artist uses her own body as part of the artwork on a plinth and waves the flag for several minutes. In doing so, she harks back to her own time as an activist in Iran in the 1970s. The performance is reminiscent of traditional Shiite rituals as well as modern revolutionary forms of protest. By applying a poem to the flag and embroidering it, Shahroudi turns it into an ‘anti-flag’ – a poetic, de-territorialised banner that describes the experiences of flight and exile.

The work ‘Max Beckmann wasn’t here’ (2019) has a similar materiality: the title of the work appears as large lettering on a banner – a reference to the German artist Max Beckmann, who fled into exile in 1937. In 2017, Shahroudi was a scholarship holder at the Villa Romana in Florence and discovered during her research that Beckmann had also worked in this studio. She shared with him the experience of living in exile, and so began an imaginary pen friendship with Beckmann. This culminates in an extensive series of drawings and the velvet banner that bears the first sentence of this dialogue with – as Shahroudi puts it – her ‘doppelganger’: ‘Max Beckmann was not here’.

The jury praised the great complexity of Shahroudi’s works: ‘With the link between the poetically over-formed banner and the expansive performance, the artist gives strong expression to her own experiences of exile in “Sky is no one’s ground”. It symbolises rootedness and connection as well as detachment and disruption. Her work ‘Max Beckmann was not here’ also uses the banner from the Shiite tradition to represent a multi-layered connection between continuity, flight and exile – both historical and contemporary. Those who have been expelled cannot be here – and yet they are through their immortalisation in art.’

Shortlist

Of the 81 impressive submissions, the jury documented the top 5 on a shortlist. In addition to the prizewinner, the works of the following artists were highlighted

Rawan Almukhtar (*1991, Iraq) is a visual artist and activist. In Almukhtar’s works, the boundaries between artistic and activist interventions are often very fine or merge seamlessly. In the large-format oil painting ‘Untitled’ (2023), Almukhtar captures a fleeting moment that inscribes itself deeper and deeper like a haunting. Using fluid imagery, he creates an emotional landscape of encounter and loss in which the experiences of flight and transformation are impressively conveyed.

Khaled Barakeh (*1976, Syria) is a conceptual artist, cultural activist and creative mediator. In his works ‘Self portrait of power structure’ and ‘I haven’t slept for Centuries’, Barakeh refers to border crossings that a passport grants or makes impossible. The artist makes wooden stamps from the stamp impressions in his passport. Stamp impressions are placed over and next to each other on a piece of paper until they cover each other and everything else. Barakeh thus thematises what a passport and the entries made when crossing the border reveal about an individual.

Parastou Forouhar (*1962, Iran) has lived in exile in Germany since 1991. As an artist and activist, she develops a variety of strategies in her work to visualise structures of violence. In her graphic, sometimes spatially staged works, she uses an ornamental visual language to show how power and powerlessness, beauty and authority are interwoven. Her long-term project ‘Documentation’ (since 1999) is dedicated to the investigation of the political murder of her parents, the Iranian opposition members Dariush and Parvaneh Forouhar, in the form of an archive.

The anonymous Iranian artist is an installation artist whose projects deal with classical Persian literature. In her video work ‘To be, or to be’ (2023), she conveys the dislocating experience of leaving something behind in a precise and impressive way. A disembodied voice, first speaking, then singing, becomes a poetic mediator between presences and absences, between performer and viewer and between darkness and the constant hope for the next sunrise.

Impressions of the award ceremony 2023

The work "Sky is no one's ground", in the background the work "Max Beckmann was not here" Stiftung Exilmuseum Berlin, Foto: Till Budde

Cornelia Vossen, Stiftung Exilmuseum Berlin; Farkhondeh Shahroudi, award winner and Thomas Paulsen, Körber-Stiftung (from left to right) Stiftung Exilmuseum Berlin, Foto: Till Budde

Cornelia Vossen, Stiftung Exilmuseum Berlin, holds the jury statement on Farkhondeh Shahroudi Stiftung Exilmuseum Berlin, Foto: Till Budde