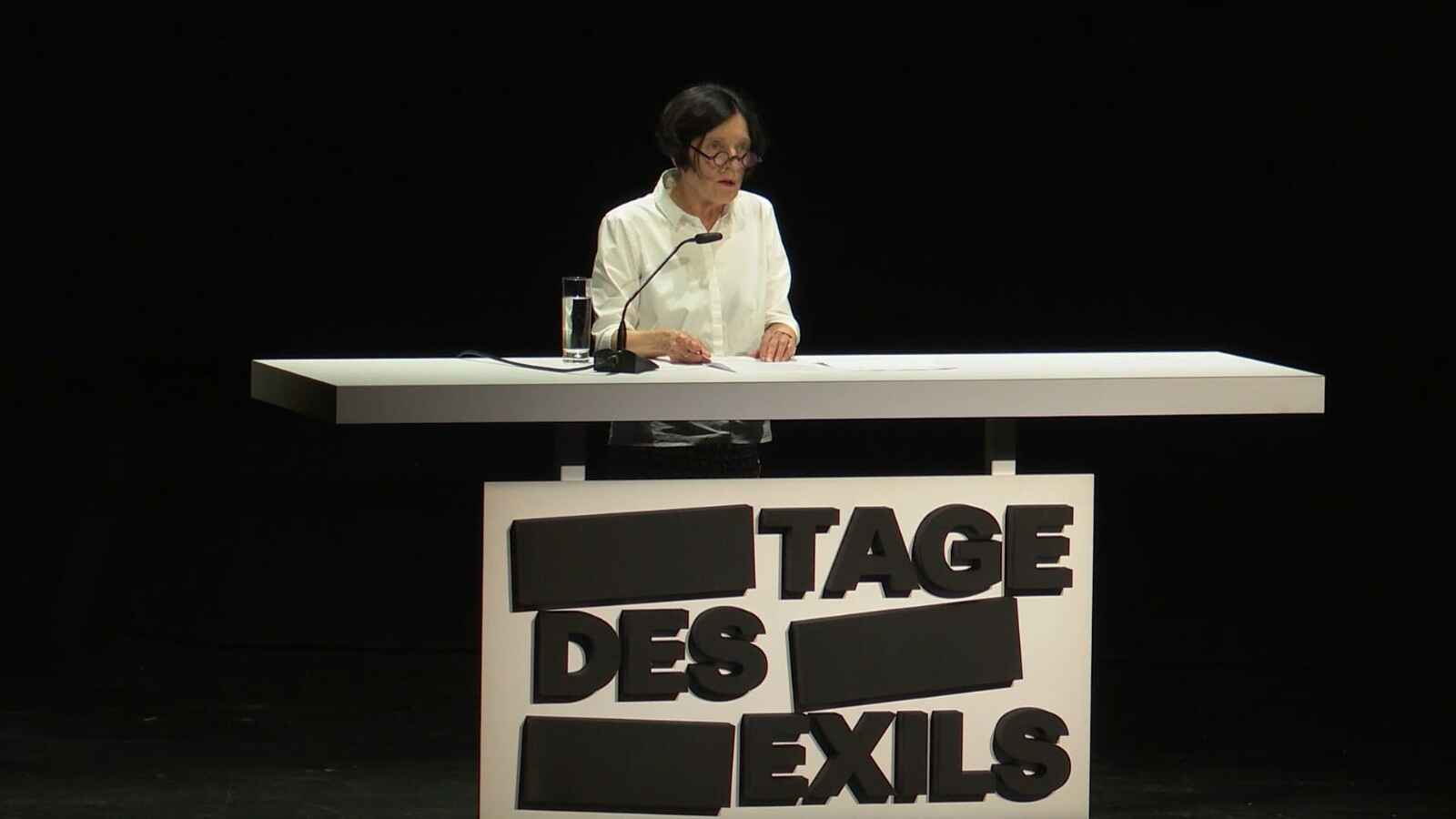

Foto: Till Budde

Speech about exile by Herta Müller

On the occasion of the opening event of the Days of Exile Berlin, on 8 September 2023 at the Akademie der Künste Berlin

The full speech on exile

The door was the first skin to be torn open

The artist Gunter Demnig has laid over 80,000 Stolpersteine since 1992. They are the smallest places of remembrance, memorial spots by the wayside. No bigger than the inside of a hand. You can usually read the name of someone murdered by the Nazis on them and very rarely the word escape to England or Palestine.

But when Demnig wanted to lay a Stumbling Stone for Walter Sochaczewski, who had fled to exile in England, a few years ago, the city of Hanover refused. The reason for this was that the Jewish paediatrician had already emigrated in 1936. He had survived the Holocaust and was not a victim of National Socialism who should be commemorated with a Stolperstein.

Since 1945, Germans driven into exile have been considered to have ‘escaped’ or been ‘saved’, i.e. not as victims. Exile should therefore be understood as the opposite of victim, even if not clearly expressed. After all, the Germans in their bombed-out cities felt like victims of the war. Those who fled were accused of having made an easy life for themselves abroad. Willy Brandt was ridiculed during the election campaign: ‘One thing you can ask Mr Brandt is, what did you do outside for twelve years? We know what we did inside.”

Willy Brandt had resisted the Nazis in exile in Norway. His real name was Herbert Frahm. He kept his exile name when he returned because exile had made him into the person we know as Willy Brandt. He literally wore his exile on his body. He said with this exile name: Just like Chancellor, I am a returnee from exile.

How much, or rather, how little is known about the resistance in exile?

For example, about the 20,000 emigrants from Germany who, like Georg Stefan Troller, Klaus Mann, Hans Habe or Ulrich Biel, joined the American armed forces in the USA to fight against the Nazis? Or Stefan Heym, who also kept his exile name and was actually called Helmut Flieg. He was one of the Ritchie Boys, soldiers who were trained in psychological warfare in America to call on German soldiers to surrender using loudspeakers and leaflets. Deployed on the front line, they were easy targets for the Nazi artillery.

Apart from the smallest memorials, the stumbling stones, the only other reminders of the flight into exile in Berlin are the slightly larger porcelain plaques on house facades. They are as snow-white as a napkin, which in dialect is called a mouth cloth.

One of these plaques hangs in Lessingstraße in honour of Nelly Sachs. It says that she lived ‘here since her childhood’ and ‘emigrated to Stockholm in 1940’.

On the one hand, this is wrong, and on the other hand, it is something that is correct but nevertheless wrong.

Nelly Sachs was neither born in Lessingstrasse nor did she live there until her exile. Her birthplace is at Maaßenstraße 15 in Schöneberg. Two years later, the family moved to Lessingstraße for a few years and again 15 years later to an upper-class flat with parlours and a fountain in the garden. The family was known throughout Berlin as the ‘Gummi-Sachse’, and had a rubber goods shop on the elegant Dönhoff-Platz. After the early death of their father, the mother and Nelly Sachs could no longer afford this flat. They rented a small flat until it was forbidden to rent flats to Jews. They found a furnished room with the Jewish widow Hedwig Rosenheim at Mommsenstraße 22 and then moved to the Pension Schwalbe at Mommsenstraße 55. 25 Jews were deported to the extermination camps from this house alone. The owners of the boarding house, Alfred and Nelly Schwalbe, took their own lives to escape deportation.

Nelly Sachs lived in constant persecution and fear of death for 7 years from 1933, suitcase in hand, trying to escape from Germany.

It was only very late, in 1940, when Nelly Sachs was 48 years old, that she and her mother managed to escape to Sweden – with the help of Selma Lagerlöf, to whom Nelly Sachs had already sent her poems as a teenager. The Swedish visa arrived just one day before the deportation was ordered. “I was lucky enough to have been in correspondence with Selma Lagerlöf since my youth. In the spring of 1940, after an agonising time, we arrived in Stockholm. The occupation of Denmark and Norway had already happened. Without understanding the language or knowing anyone, we breathed in freedom.” – said Nelly Sachs in her speech at the Nobel Prize ceremony in 1966.

In the text ‘Life under Threat’, she describes the constant fear of death during the seven Nazi years in Berlin. “Time under dictation. Who dictates? Everyone! With the exception of those lying on their backs like beetles before death. … Footsteps came. Heavy footsteps. … Footsteps banged on the door. Immediately they said, time is ours! … The door was the first skin to be torn open. The skin of the home.”

From her first day in Sweden, Nelly Sachs did everything she could to leave the horror behind her. She learnt Swedish very quickly. Her poems were transformed by the influence of modern Swedish poetry. She began to translate Swedish poetry into German. Hilde Domin writes: ‘Anyone who has experienced exile immediately understands the intimate identification that arises from the combination of the two languages: that of the lost home and the country of refuge. Something is created that softens foreignness and gives people a place that no longer has one. … She is therefore an exile poet not only in the sense that she suffered exile and thematised it. But that exile literally became her artistic rebirth.”

Nelly Sachs left Nazi Germany with her feet and took her head with her.

And the horror was prolonged. Not just her own. From 1943 onwards, the gruesome news about the extermination camps and the deportation to death began to arrive.

In Stockholm, Nelly Sachs lived with her mother on the third floor of a small flat of only 40 square metres in a house belonging to the Warburg Foundation and inhabited almost entirely by German-Jewish refugees. To earn a living, she worked as a laundress and translator. When her mother died, she completely lost her inner stability. The persecution mania reared its ugly head. She felt surrounded by the Nazis. In a text written in Swedish in 1960, she wrote: ‘For about a year now, a cutting noise has been heard from the tap in the kitchen. I couldn’t localise whether it was above or below my flat. But I didn’t get the impression that it had anything to do with daily housework. … Could such an organised noise be a coincidence? … A workshop had taken up residence above my flat. … The worst thing about it is that so many people are involved and I am completely helpless. A collection of hitlers on a small scale and immense cowardice.” Nelly Sachs hears Morse code signals from a National Socialist command centre throughout the house. She only walks through the streets wearing a headscarf and earplugs and sees blood in the red traffic lights. And she now receives psychiatric treatment again and again. Even in closed wards. It was during these times that Nelly Sachs wrote her poems about the persecution in Berlin. It seems that writing keeps her alive.

SO RANN ICH from the word:

now it is late.

the light goes out of me

and the heavy too

the shoulders are already travelling

away like clouds

Arms and hands

without carrying gesture

The colour of homesickness is always deep and dark

so the night

takes possession of me again.

Aris Fioretos says that for Nelly Sachs, writing was a ‘relief that threatened her at the same time.’ When you read this sentence, it is no coincidence that you immediately think of Paul Celan. Nelly Sachs and Paul Celan had a lifelong close friendship. It was a mutual dependence between two lost people who were tormented by the memory of the extermination of the Jews. And it was an unconditional closeness, a dark and abysmal commonality.

In one of her severe crises, Nelly Sachs sent a telegram to Celan in Paris asking him to come to her in hospital. And Celan does come. But Nelly Sachs is too deeply confused. She does not receive him because she does not recognise him.

Although the two texts are completely different, they nevertheless meet – one might almost say – emotionally. Nelly Sachs’ style is ecstatic, a language out of itself. Hilde Domin writes: ‘The ecstatic does not have the poem in his hands, rather the other way round. … For him, the poem is never a doing, always a doing in which he is carried away. … Celan, for example, compared to her, is a doer, an artist. Which is not meant to be a judgement.”

In the letters, the two share not only their concerns about each other, but also their new poems. One letter to Celan contains the poem:

Who is calling?

Your own voice!

Who answers?

Death!

Does friendship perish

in the army camp of sleep?

Yes!

…

What is that?

Sleep and death are featureless

And then the poem turns into a letter:

‘Paul, before I return to the flat in two days – on trial – whether I may live in freedom again – this greeting from the hospital – and blessings for you three – my beloved family.’

And in the poem cycle ‘Glowing Riddles’ she writes

1

This night

I went into a dark side street

round the corner

There my shadow lay

in my arm

This tired garment

wanted to be worn

and the colour nothing spoke to me:

You are beyond!

2

Up and down I go

in the warmth of the parlour

The lunatics in the corridor screech

with the black birds outside

about the future

16

When I leave the parlour protected by illness

I will leave – free to live – to die –

…

I do not know

what my invisible

will now do with me –

In 1960, Nelly Sachs receives the Meersburg Droste Prize.

She returns to Germany for the first time in 20 years. She flies to Switzerland to travel to the award ceremony from there so as not to be in Germany for too long. And yet the journey ends tragically. Aris Fioretos says that the Droste Prize was a ‘lucky catastrophe’ for her. After reacquainting herself with Germany, the ‘beloved and feared country’, her mental illness worsened. She was hospitalised for a long time. But in Switzerland, she met Paul Celan at the Hotel Zum Storchen. As with him, Nelly Sachs’ growing recognition “coincided with a feeling of increasing persecution” (Fioretos). Celan wrote the following poem to her in the clinic:

ZURICH, ZUM STORCHEN

For Nelly Sachs

There was talk of your God, I spoke

against him, I

left the heart I had,

hope: for

his highest, rattled, his

quarrelling word –

Your eye watched me, looked away,

your mouth

spoke to the eye, I heard:

We

don’t know, you know,

we

don’t know,

what

applies.

Nelly Sachs also received the Peace Prize of the German Book Trade and was made an honorary citizen of Berlin shortly before her death. But Hilde Domin says that the more she was appreciated, the more she was ‘de-embedded’.

There are coincidences that should not exist. Celan probably died in the Seine on 20 April. But what is certain is that his funeral was held in Paris on 12 May 1970. On the same day, Nelly Sachs died in Stockholm.

Someone comes from afar

Comes one

from afar

with a language

that perhaps the sounds

closes

with the neighing of the mare

or

the cheeping

of young blackbirds

or

also like a crunching saw

that cuts through all closeness

…

A stranger always has

his home in his arms

…

For Nelly Sachs, this is all part of the short word exile. And she is just one of 500,000 Germans who were driven out of Germany by the Nazis.

You can’t explain on a china table that you were fair game, that you carried your despair from one hiding place to another, that good or bad chance played a role in your fate. And that even in a good coincidence you arrived in a hopeless foreign land with shattered nerves. That you were ‘saved’ poor and lonely, without the strength to hope, surrounded by your own forlornness.

There is now a museum dedicated to the expulsion from the German eastern territories to Germany – the Museum of Expellees. But they were the second displaced persons. The first expellees were the ones chased out of Germany. Wasn’t Germany their homeland? Were they not also expelled?

When we talk about exile today, we are still talking about this blank space in the German culture of remembrance. The palm of the Stolpersteine and the mouth cloth of the porcelain plaques are too small to show the dimensions of exile. We need the Exile Museum at Anhalter Bahnhof. We need it for the exile of the past and also for the exile of today. Because as long as there are dictatorships, there will be flight and exile. Again and again. By remembering the exile of the past, we learn to sympathise with the exile of today. In this sense, the Exile Museum is in itself also a museum of the present.